I made a stab at building EMBOSS

According to the adminguide, it requires zlib and libpng as well as gd. Since EMBOSS is set up for Linux, I will probably have to edit the config file to show where these libraries are on my machine.

I installed zlib and libpng to get matplotlib up and running (according to Gavin Huttley's wiki instructions).

Let's get gd. Downloaded gd-2.0.35.tar.gz from this page. According to the readme, it's the usual:

(using sudo). And it has a problem:

It seems to be related to a library called Fontconfig.

Get fontconfig-2.8.0.tar.bz2 from here. According to INSTALL do:

but it fails because there is no configure, why not? From a web search it seems that

autoconf processes configure.in to produce a configure script

so I try this:

and then do as before:

It looks like I'm supposed to use autoconf, but first I have to fix the above error.

After another web search, try adding this to configure.in

autoconf goes fine. Now:

And I'm stuck. You can't feed fontconfig to AM_INIT_AUTOMAKE.No EMBOSS for me, it seems.

[UPDATE: I found instructions for installing GD here. It turns out I already had /usr/X11R6/include/fontconfig. The test of GD looks fine.

Followed simple instructions for EMBOSS and did:

And after searching around for 10 minutes I finally ran:

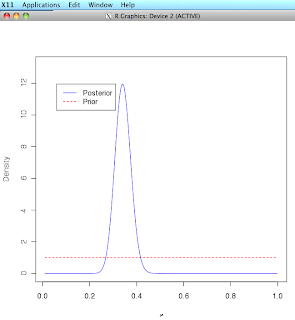

Now I have a window to play with (graphic at top of post)! ]